Chapter 13

Carlos’s eyes kept on stinging, though the crying has already stopped. He looked to Mai. She smoked in quiet contemplation, watching the faint swaying of leaves and grass outside the glass backdoor, in the meticulously scaped yard. Bé was in the kitchen. She retrieved from the fridge an oven tray of brownies. Three fourth had been carved out, but there was still plenty left to go around. She wiped her still reddened nose with a backhand and chuckled. The offer had occurred naturally while the three were a heap of emotional mess, strewn about on the long couch. Mai had asked if she could smoke in the house. Bé confessed to her own vice, and before they knew it, some special treats were in order.

Each of the three took out a meager spongy cube from the brownie tray. Carlos nibbled slowly. He had taken these before, but none ever tasted so sweet and aromatic. Cathartic satisfaction made things much more rewarding, much more worthwhile. While the women talked, he became sharply aware of the emptiness inside of him, but it wasn’t the sort of void where it consumed a person from the inside. Rather, it was by nature the very lack of business, of occupation. It was freeing and accepting, and he was too. Bé went over to put some music on the cottage’s uncharacteristically elaborate sound system. It wasn’t like anything that Carlos nor his youngster friend group was used to, in other words deep house. He wondered if Mai liked what was playing. A prolonged and droning sitar wailed them all the way to the distant Indian Subcontinent. Dirty industrial basslines supplemented mystic chants. It sounded like what would play in an S&M dungeon that doubled as a yoga class, but Carlos couldn’t help losing himself in this wall of sound. He didn’t get around to asking who was playing that day.

They felt it now, an hour later. All chatter has halted as time seemed to have stretched infinitely long. A minute composed of many seconds, and seconds themselves were made of milliseconds, then nanoseconds. Every single ticks, Carlos felt to have sludged by and waved hello to him, personally. The room rotated on an invisible axis, gyroscopically stabilized. The women sipped on their herbal tea and shared a lucky, lucky cigarette between themselves. When Mai and Bé started talking again, they did so deliberately, yet out of random; conversations had not a clear beginning and seemingly hinted at no end. He, too, was full of words, the most magnificently dear and enlightening words, but he couldn’t seem to find an opening, nor the impetus to initiate. He reminded himself that he preferred to listen. So he listened, letting the uttered incantations flow through his mind like an impenetrable substance that he embraced and accepted fully. His bliss didn’t come from this ignorance, but rather from the liberation from worry and fear, and from letting bravery and love plunge him deep into the lives of others. Their words and sentences and ideas had a clear pattern, repeating itself in everything else in the room, a sacred mantra that all were born into and did their best to carry the torch, mother to daughter, and the daughters thereafter. In this faint realization, he glimpsed the extent to which his own Ātman was intertwined with the roots of the life-giving tree at the spine of being. He realized that deliverance from destruction had only one path, and it was to welcome the very inner annihilation. The boy knew that he, Mai, and Ms. Mulway would conquer death, and in some vicarious way, Hà would too.

ॐ त्र्यम्बकं यजामहे सुगन्धिं पुष्टिवर्धनम्

उर्वारुकमिव बन्धनान्मृत्योर्मुक्षीय माऽमृतात्

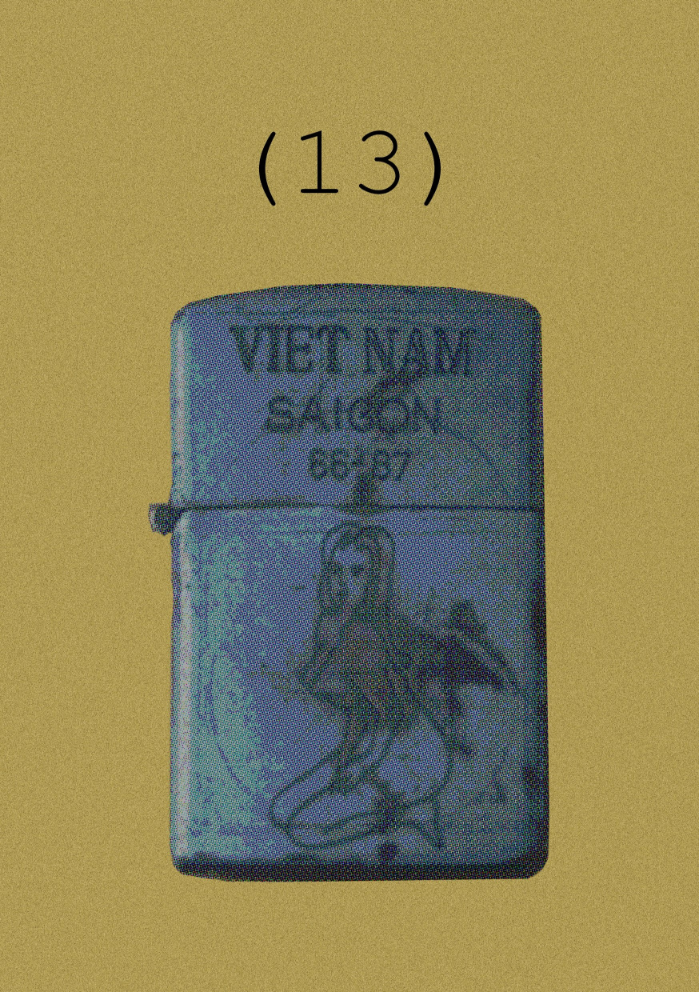

Mai had her arms draped around Bé. They blended into the upholstery as if their flowing hair and supple limbs have always belonged there. Among the black manes where two pairs of red gems watching the world go by invisibly. Mai was idly fidgeting her Zippo, thumbs rubbing at the “Saigon” inscription as to erase those letters from the metal face. What was left of her forgotten cigarette was a grey finger of ash curling towards the ashtray’s tin bottom. Noticing the curio, Bé lifted the Viet girl’s hand to inspect her worn lighter.

“That’s pretty,” the woman commented. “Most of these Vietnam-type Zippos all have such crude engravings. Always a reference to the war.”

“Funny thing, this wasn’t her first choice. My mom wanted to buy one with two nude women in a tub. That one was supposed to be ‘Saigon, 1975’. I thought it was funny, but she had second thoughts. Opted for the boring one instead. Guess she was tired of the same old, so after a few years, she gave it to me.”

“Mm, that’s interesting. Why wouldn’t it say ‘Huế’ though?”

“We moved to Saigon really early on. No one liked Huế, to be honest.”

“It was beautiful when I was there.”

“Try living there,” Mai deadpanned.

“You have a point.”

“And my mom’s snark.”

“Was she, really? I guess everything is rosy in hindsight,” Bé admitted. “I’ve always remembered her as super straight-laced. OK, maybe a bit snarky.”

“You know, maybe? Maybe who you met before was a different person.”

“Ha, are you saying I’m not the person you’re looking for?”

“I mean, after we moved and the eventual divorce, she bought a Zippo, then took up smoking and drinking. That doesn’t sound ‘super straight-laced’, if I’m being honest.”

“Geeze,” was all Bé could muster in her state. A prolonged delay ran its course before Mai put a cap on the thought.

“If it’s any consolation, she lived a good life. She got a career that she was proud of, and things were peaceful at home.”

“Yeah, you told me on the phone.”

“Mm,” and that was that. Mai laid her head on the woman’s arm again and closes her eyes, then said, “The funeral was stupid.”

“Oh, I’m sorry. Why?”

“Just like weddings; a hundred people wanted a hundred different things. Like shit, I’m her only child, right? So I’m smack-dab in the middle of the mess. They expect me to basically handle everything, yeah? And there I was, jetlagged as all fuck, being asked left and right why I wasn’t crying. I knew for a fact that some of them came for the food.”

“Relatives can be shitheads sometimes, honey,” Bé contemplated, sounding as though she only knew too well.

“They made an awful show of it. Sometimes, I think, mom didn’t even have a proper funeral, even. I was the only one who gave a proper shit, right? But I couldn’t even focus on mourning. So it’s just gnawing at the back of my skull, like she’s still there, kind of a nagging presence. Like I’m supposed to put her to rest, but how? I’ve got all these mementos (flicking the Zippo) and jack shit to do with it,” Mai sounded exhausted. She then looked over to her boyfriend and said, “It’s not even mine. I gave the thing to Carlos there a while back.”

And so, in that brownie haze, Carlos felt a jolt through his tendons and ligaments running from head to feet. He saw it in the mature woman and his petite sweetheart too, that same spark that was unmistakably the conception of something so brilliant that the three just had to shout out at the same time.

…

In the cottage’s backyard, the trio gathered for their impromptu funeral. Carlos was digging a small hole with a rusted trowel, where a rose shrub met the edge of the back pond. Mai had said the water and flower had some relevance to her mother. The boy only eagerly obliged. This would be where the Saigon lighter would rest eternally, being one with the earth that made up its components. They picked a fist-sized rose and placed it along with the Zippo. Carlos filled up the gap with loose dirt and grass, making a little mound on the damp black soil. It was almost poetic, he thought. His body was still buzzing and feeble. He focused on maintaining his posture, trying his best not to fall into the rigid water and ruin the severity of this moment. The sun was setting again, making the distant cloudhead a hue of ember over a darkening sky. Like ember, the light was fading fast.

“You know, what sucks?” Mai asked nobody in particular.

“What?” Bé obliged.

“She always talked about a grandchild. It’s the one thing that I refused to give to her. We fought so much over it.”

“Honey, don’t beat yourself over it. Everyone has to go their own way.”

“So many missed firsts.”

“Can we ever do everything?”

“I’m trying,” and with that, they stood in silence.

The last faint sunray narrowed until nothing remained but black shadows upon an eternal stretch of blue. Three silhouettes stood around a rose shrub and a twinkling pond. Bé confessed her hunger, and they went inside in search of food.